The Classic Fairy-Tale Journey: Psyche’s Descent

Exploring the beats of the Brothers’ Grimm fairy-tale journey

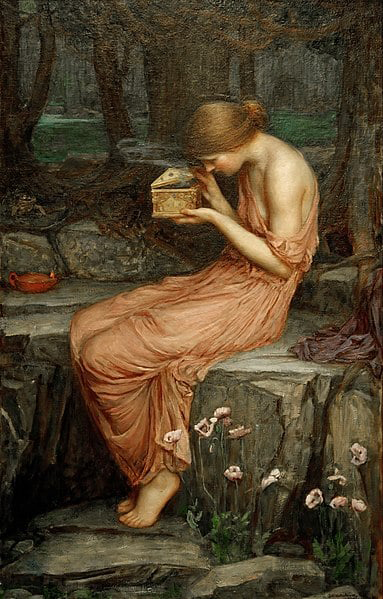

There is more than one variant of the Heroine’s Journey, aka the Fairy-Tale Journey. There’s the oldest version, modeled after the Descent of Inanna. Let’s talk now about the youngest version, with the only literary version coming to us from the Second Century A.D.(although there are artistic images from the last ~500 years of the B.C. era).

This youngest version is similar to what people usually think of when they think of fairy tales: a Brothers Grimm story. If you’re a fan of mythology; however, and Greek mythology in particular, one tale stands out as an archetype oF the Brothers Grimm: Psyche’s Descent. Indeed, it’s impossible to read of Psyche’s journey without also thinking to yourself, “This seems like something I would have read in the Brothers Grimm.”

Note the similarities:

- Psyche is a princess who is the youngest of three daughters. Through no fault of her own she arouses enmity in Aphrodite, because people believe her equal to Aphrodite in beauty.

- The Oracle of Apollo says she will marry a monster. Aphrodite attempts to make this propehcy true, by commanding her son Eros to smite Psyche with an arrow to make her fall in love with something odious and demeaning to her.

- When Eros tries to carry out the command, he is pierced by his own arrow and falls in love with her.

- With bitter tears, Psyche’s family conducts her to a cliff, where she is to be left alone, to marry her unseen, monstrous husband. The West Wind conducts her safely to a valley below, where she finds a divinely wrought palace filled with magical, unseen servants who attend to her every need.

- Never does Psyche see the face of Eros, and she is forbidden to seek it. Thus, she doesn’t know if he’s a literal monster, or a man of monstrous appearance.

- Three times Eros warns against Psyche allowing her sisters to visist, on the grounds that they will bring destruction to both of them. But three times Psyche prevails, and three times Eros extracts a vow from her not to betray him. The final time, Psyche is with child, and Eros tells her she will bear a god if she keeps the promise, or bear a mortal if she betrays him.

- On each occasion when Psyche’s sisters visit, Zephyrus, the West Wind, carries them safely to the valley when they jump from the cliff.

- Visiting Psyche in her divine palace awakens envy and malice in her sisters, who are not satiated by the finery she bestows on them as gifts. They seek to usurp her place as the wife of Eros, and take her wealth for themselves.

- Naturally, Psyche’s envious sisters trick her into thinking Eros is truly a serpent who will devour her, and they convince her to betray her husband. She stealthily creeps up on him as he sleeps to see his face at last, and accidentally pierces herself with one of his arrows. Naturally, her love for him increases exponentially. But the oil from her lamp drips on Eros and the burn awakens him. Enraged, Eros flies off to his mother’s house.

- Upon learning that Eros abandoned Psyche, her sisters abandon their own husbands and rush to the cliff overlooking the valley. As punishment for their envy, greed, and deceitfulness, Zephyrus ignores Psyche’s sisters when they jump off the cliff. Pieces of their bodies scatter to and fro, as food for beasts.

- Three times Psyche meets a god. Pan gives her useless advice, though she pays him obeisance anyway. She cleans the temples of Demeter and Hera, who are kind, but refuse to give her refuge because Aphrodite is kin to them and they won’t betray her.

- When Psyche surrenders to Aphrodite, who had placed a bounty on her, the goddess gives the princess three impossible tasks. In these tasks, Psyche is aided by friendly creatures and spirits.

- In the final task, of going to the realm of Hades to retrieve a jar of Persephone’s beauty, Psyche succumbs to Aphrodite’s treachery. She opens the jar and is punished with endless sleep. She is awakened from eternal slumber by a kiss from Eros, who finally recovered from the oil burn.

- Because of his love for her, Eros asks Zeus to grant him eternity with Psyche. Zeus obliges, by giving Psyche ambrosia so she will become an immortal goddess. She and Eros wed, and she gives birth to their daughter, Pleasure (Hedone).

Do let me back up a second and point out that while Eros is not physically monstrous, his character and behaviour is described in-story as monstrous, for he wantonly destroys marriages by smiting people with arrows so they fall in love with other people besides their spouses. But otherwise, do try and tell me that Psyche’s tale isn’t the archetype for Brothers Grimm, or a Disney Princess movie. Go on!

So now we will delve into the narrative structure behind the classic stories Psyche inspired. Remember that “classic” refers to enduring works that have stood the test of time, and the goal here is to write stories that can stand the test of time. So let’s learn, shall we?

In my quest to learn more about the Heroine’s Journey, and how it might be used narratively, I stumbled across Dr. Theodora Goss, a novelist. She listed the steps the Journeyer takes in a Psyche / Grimm-style Journey, and has a lot of insightful things to say about this structure.

However, I was uncertain at some points where these beats might fit into a narrative, and that was how I ended up finding Ookami Kasumi, a blogger and artist. She studied fairy tales to find out about female-centric adventures. Kasumi’s post placed the steps in a structural order, and she made a cool graphic that really puts it all in perspective. You can find it on her post about the Journey.

I took a little from Column A, and a little from Column B to make this post. I found in reading their sites that Goss and Kasumi approached these steps from different angles. Frequently one fleshed out an insight pointed out by the other. I’ve joined their posts together, and I will state up front that any errors are mine, particularly in instances where I paraphrase them.

Regarding what the structure of Psyche’s descent / Bros. Grimm fairy tales, Goss pointedly remarks that the structure isn’t universal to all fairy tales: it doesn’t appear in every era in every society. She carefully says of this particular journey structure:

…that if we examine a particular subset of European fairy tales, we find a pattern of narrative elements constituting a “fairy-tale heroine’s journey.” This subset is small but important: it consists of fairy tales that focus on women’s lives, from childhood to marriage, and includes some of the most popular tales that have come down to us from fairy-tale writers and collectors such as Charles Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, Madame de Beaumont, and Alexandr Afanas’ev.

They are important because for generations, they have presented to girls and women what society considers the natural pattern of a woman’s life. They have done so directly as literature for children, but also indirectly, by influencing adult fiction written for a female audience. This is the pattern of “Cinderella,” “Snow White,” and “Beauty and the Beast”: it is also the pattern of “Jane Eyre.”

In the post linked above, Goss elaborates a key point regarding a particular aspect of the fairy tales:

Fairy-tale heroines learn housework and needlework because that is what most European women learned in the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. Even my mother, who grew up in nineteen-forties and -fifties Hungary, thought these were necessary skills for her daughter. She also told me about the gifts young girls would receive on special holidays or at particularly life stages.

Heroines leave or lose their homes because women did leave — lower class girls to become servants or apprentice themselves to trades, upper class girls to schools or convents. What we are seeing, I believe, is the pattern women’s lives took at a particular period in time, turned into fantastical narrative. This includes both physical and emotional life stages.

Dark forests did stretch across Europe; however, we have all also entered the dark forest metaphorically. Fairy tales are grounded in ordinary things, such as bread, trees, spinning wheels, and ordinary experiences, such as hunger, death, love. The fairy-tale heroine’s journey tales are no different.

For clarification, what Goss refers to as the “Dark Forest,” Kasumi refers to as the “Labyrinth.” Dark Forest is consistent with the Brothers Grimm-type fairy tales. Labyrinth is consistent with fairy tales involving mythic figures, such as Inanna, Psyche, Demeter, and Isis. I’ll get to Demeter and Isis in another post, focusing on Gail Carringer’s version of the Heroine’s Journey.

Final caveat, I use the Four Act structure for emphasis on where some of these beats may fall into. Of course, do note that not every step needs to appear in your own story, and some steps may appear more than once.

Enough head words, onward to the “recipe!”

Act I: Ordinary World / Setup

- Once Upon a Time, a Secret Betrayal:

- (Kasumi) Fairytales begin with the heroine being secretly betrayed, often by someone who envies her. Other times, her male relatives trade her skills for cold, hard cash.

- The Herald, Bearer of Bad News:

- (Kasumi) This is the Catalyst: a friend, family member, enemy, or object that reveals the deed, promise, or debt for which she is being held accountable, or the deadly danger she’s being sent into.

- The Heroine Leaves or Loses Her Home:

- (Goss) Donkeyskin leaves home to escape her father. The Goose-girl leaves home to be married. Cinderella loses her home when she is forced to live in the kitchen and sleep on the hearth. No one on the heroine’s journey is permitted to Refuse the Call, and they frequently don’t want to.

- Mentors, Tricksters & Costly Gifts:

- (Goss) Sleeping Beauty receives gifts from the fairies. Donkeyskin receives three dresses from her father and a ring from her mother. Cinderella receives three dresses and magical shoes from the hazel tree. KASUMI: In all cases, there is a life-altering price on such gifts. Sometimes the payment is a trinket such as a necklace or ring, but more often it’s a promise to be delivered later, or a first kiss—meaning her virginity.

- First Plot Point | The Heroine Enters the Dark Forest:

- (Goss) There is almost always a dark forest. It is usually where the heroine loses her way, but also where she finds friends and helpers and potentially, a place of refuge. This stage is the point of no return for the heroine. Kasumi: She gives in to temptation and takes the offered gift, crossing the threshold to the labyrinth and committing herself to a path where there is no turning back. This scene can be played out as a rescue, which usually includes the demand of a reward such as a kiss—the symbol for outright seduction.

Act II: The Dark Forest

Act 2-A (Reaction) — Secret Allies, Secret Enemies, Deadly Gifts & Scary Promises

- The Temporary Home:

- (Goss) In the Dark Forest, these heroines find temporary shelter and, often, learn whatever they need to before they move on. In this shelter, the heroine learns to work: Snow White and Cinderella keep house. Alternatively, she wants to work, but can’t, e.g., Sleeping Beauty tries to spin and ends up cursed.

Note, the work isn’t necessarily domestic: in Charlotte Rose de la Force’s “Persinette,” the girl in the tower is taught the accomplishments necessary for an upper-class young lady, such as reading, painting, and playing musical instruments. - The heroine finds friends and helpers:

- (Goss) Snow White’s dwarves, Cinderella’s doves. The head of a dead horse, three old women by the roadside, the winds themselves — all sorts of people and things can be friends and helpers. Fairy-tale journey heroines rarely have to solve their problems alone: there is almost always someone to help them or keep them company.

- Temptations & Trials:

- (Goss) Temptations are what the heroine must resist; trials are what she must undergo or overcome … Over and over, it includes the possibility of dying, or loss of family. Kasumi: Another gift is offered with an even higher price-tag, a more chilling promise, e.g, . Cinderella arrives at the ball to seduce her prince, but has promised to leave by midnight. She has every intention of fulfilling her bargain, but she has secret enemies.

- Treachery / Broken Vows:

- (Kasumi) Through trickery, lies, theft, temptation, ignorance, or outright willfulness, her promise is broken: While the clock is striking twelve, Cinderella finally notices the time. Sometimes the heroine keeps the vow: Vasilisa sees nothing she’s not supposed to in Baba Yaga’s house; she has a doll to do the dangerous tasks for her.

- Midpoint | Crash Point, Center of the Labyrinth / Dark Forest:

- (Kasumi) Aware that she must pay the price for her broken vow, she bravely goes forth — to find a way to dodge the consequences: Cinderella bolts for her clay horse knowing full well that it won’t make it all the way home.

2B: Attack

- Ordeal | The Heroine Dies or is in Disguise:

- (Goss) Snow White dies, Sleeping Beauty falls into a death-like sleep. The Goose-girl is not recognized as a princess. Cinderella is not recognized as herself (despite having danced with the prince for hours).

- The heroine is revived or recognized:

- (Goss) Dead heroines are revived (Snow White, Sleeping Beauty), lost heroines are recognized (Donkeyskin, Cinderella). Often the one who revives or recognizes the heroine is her true partner, but Vasilisa is saved by her mother’s blessing, and Mother Holle’s servant returns to the land of the living after having completed her tasks in the underworld. Kasumi: If she survives the Ordeal, she is rewarded with release from the heart of the labyrinth — or punished by expulsion. Either way, she is permanently marked by her experience.

Act III: Restoration

- Leaving the Dark Forest / Finding her true partner:

- (Kasumi) She heads back to the Ordinary World with a mission to accomplish. At the last threshold, she replays her very first act of commitment, a keepsake gift, a vow, or a kiss. Goss: Apropos of the kiss, Goss specifies this stage is the one where the heroine marries an upper-class man, who is her true love. Sometimes this stage is an entire subplot, in which the heroine must first lose and then find her true partner.

- The heroine’s betrayer is punished:

- (Kasumi) She returns to face her original betrayer. She needs them to acknowledge what they have done to her. This scene is often played out as a visit to her home in her bridal finery and a huge feast. However, this is also when the wicked are punished. Goss: The punishment is usually, actually or metaphorically, created by the tormentor herself.

- The Last Promise and Ever After:

- (Goss) The heroine finds her true home, where she will live happily ever after. It is usually a castle. Kasumi: After all her final goodbyes are said, she returns to the Labyrinth (Dark Forest) to take her place there and receives one last gift, normally a crown or wealth, and makes one final promise. Sometimes it’s merely a wedding vow, sometimes it’s not. Snow White et al vow to be good queens, Vasilisa becomes the Tsar’s advisor and vows to always tell the truth.

Concluding Thoughts☍

Regarding the Ordeal, where the heroine dies, note that the death need not be literal, just as it needn’t be in the Hero’s Journey. As with the Hero’s Journey, the death is symbolic. Here Goss notes that in the fairytale, the “death” represents a girl’s rite of passage to womanhood in more traditional societies. The rites marked when the girls became eligible to marry, and accordingly, the fairy-tale heroines “die” or undergo disguises when they are old enough to marry.

Arnold Van Gennep showed that such rites often involve a symbolic death: the participant symbolically dies in one social state and is reborn in another.

However, there are exceptions to the heroine being the one who is in disguise or must be revived. Goss cites East O’ the Sun and West O’ the Moon as a story where the heroine’s love interest is both in disguise and symbolically dead, and the heroine is the one who does the reviving. I’m not familiar with this particular tale, but the Goodreads description at the link has piqued my interest. In the meantime, this completes the tour of Fairy-Tale Journeys, at least for now. After all, there are a good many variations of fairy tales out there. That said, here’s another tool for your writer’s toolbox.

Further Reading

- Beat Sheet: Psyche’s Fairy-Tale Journey

Download includes PDF, .doc, .docx, and .page versions of the beat sheet