Mythic or Fairy-Tale Journeys for Heroes and Heroines

Which journey is your character undertaking?

How to determine if your character is taking the Hero’s Journey, or the Heroine’s Journey

The sex of your character will have nothing to do with whether or not they will undertake the hero or heroine’s journey. Those journeys are unisex, even though at first glance it would seem the Classic Fairy Tale outlined by Dr. Goss and Ms. Kasumi are only suited for female characters.

Steve Rogers in Captain America: The Winter Soldier, and Prince Zuko in Avatar: The Last Airbender are men on Heroine’s Journeys, of the type outlined by Victoria Lynn Schmidt. That is to say, they are personally under threat from an enemy they must deal with. In Captain America’s case the enemy is Hydra, in Zuko’s case the enemy is his father.

Wonder Woman (first movie) is on the Hero’s Journey, as is Joan Wilder in Romancing the Stone; in both cases the women are attempting to save others from an external threat. In Wonder Woman’s case she’s trying to save the world from Ares, in Joan’s case she’s trying to save her sister from the evil men holding her captive.

Why can the journeys be unisex? The actual difference between them has to do with whether or not a journey is a fairy-tale journey, also called “the heroine’s journey,” or a mythic journey, also called “the hero’s journey.”

Fairy tales concentrate on obligations to the self apart from a group: one’s own autonomy, self-worth, and identity. Myths focus on obligation to others, and self-sacrifice in protecting the group.

The clue to which journey, then, has to do with the stakes of the story, the setting, the nature of the protagonist, and the impetus for the journey. For those of you who like the fantasy genre, I liken the differences between myth vs. fairy tale to that of sword & sorcery (Conan the Barbarian) vs. high fantasy (Lord of the Rings):

Point being that fairy tales are similar to sword and sorcery, with domestic problems affecting one person or their family. Myths are more like high fantasy, with problems that affect the world at large, and may require assembling the Avengers.

Somewhere, Over the Rainbow vs. Right In My Own Backyard

In a fairy tale / Heroine’s Journey, the “Ordinary World” is dysfunctional. It’s negative, and stunts the main character. There’s a corrupt core to its glittering façade; Something Is Rotten in Denmark. The Protagonist must undergo an inner transformation to claim personal autonomy and change their status quo.

This change is undertaken within the domestic realm — Right in My Own Backyard. It doesn’t matter if the backyard is a space ship, e.g., the Nostromo in Alien. The “quest” is for self-actualization. Think of Danaerys Targaryen’s arc in the books. (I gather the show diverges significantly from the books). Or Queen Cleopatra Selene’s Isis Journey arc in Stephanie Dray’s Song of the Nile.

In real life, historians believe Selene sought to take the throne of her mother, Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt. But Selene never achieved that goal; she was “only” queen of Mauretania, which she ruled jointly with her Berber husband, Juba II. In Dray’s telling, Selene goes from vengeful schemer to a woman at peace with her fate, and this peace comes as a result of her taking the Heroine’s Journey. Schmidt and Hudson both cite Tess in Working Girl as another example of a character undertaking the Heroine’s Journey.

In contrast, in the mythic Hero’s Journey the Ordinary World is often functional. It’s nurturing and supportive of the hero, and it’s worth protecting. The protagonist frequently lives in a place akin to “the Shire,” the bucolic land in which the Hobbits live in The Lord of the Rings. In Hero’s Journeys, “the Shire” will be imperiled by an outside force. The protagonist must make an inner transformation in order to protect the kingdom’s status quo. Frequently, the protagonist is required to go on a quest into the unknown—Somewhere, Over the Rainbow. This is the “mythic” structure. The journey is about self-sacrifice for the good of others.

In other words:

- Hero’s Journey =

- Somewhere, Over the Rainbow

- Heroine’s Journey =

- Right In My Own Backyard

- The Ordinary World in the Hero’s Journey =

- The Shire

- The Ordinary World in the Heroine’s Journey =

- Something is Rotten in Denmark

In Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell himself says the following:

…the hero of the fairy tale achieves a domestic, microcosmic triumph, and the hero of myth a world-historical, macrocosmic triumph. Whereas the former—a youngest or despised child who becomes the master of extraordinary powers—prevails over his personal oppressors, the latter brings back from his adventure the means for the regeneration of his society as a whole.

Emphasis mine. Campbell breaks down the different mythic heroes. If tribal, they bring the boons to a single group, e.g., Moses delivers the Israelites, and brings them the Law from Mt. Sinai. If universal they bring a message to the entire world, e.g., Jesus, who gives the Great Commission.

Schmidt noted that the Heroine’s Journey lends itself very well to Final Girl horror, or thrillers. She has a point. Horror stories frequently take place in one’s own backyard. Horror scenarios are usually thrust upon a character; a character does not go in search of them like a quest. In the first four books of the Vampire Diaries (when the real author, L.J. Smith, was still writing them), Elena Gilbert must save her hometown of Fell’s Church from vampires and werewolves. In Dan Simmons’ Summer of Night, the boys of the Bike Patrol must save their town from an ancient evil. Their modern successors in Stranger Things save their town of Hawkins from the Upside Down.

In The Virgin’s Promise, Kim Hudson sums mythic stories like so:

Myths are centered on themes of place in the world of obligation. This is the realm of the Hero as he seeks to answer the question, “Could I survive in the greater world, or am I to forever cling to the nurturing world of my mother for fear of death?” His journey is towards physical independence.

The Hero must push and tempt the boundaries of mortality—and as immortality is the realm of the gods, the Hero will frequently battle seemingly immortal villains.

For the sake of clarity, I’m going to refer to the hero or heroine as “the Journeyer” to further underscore that the protagonist in a Hero or Heroine’s Journey can be female or male respectively.

The Price of Failure

In a fairy tale, the stakes are personal. They may be as simple as saving the family farm, or the right to live free rather than as a slave to one’s evil stepmother. Failure will result in alienation from family or society, to the point of personal misery at best, and suicide at worst.

In a myth the stakes are collective, and failure may result in the destruction of a village, or the whole world. If Frodo does not destroy the One Ring, all of Middle Earth will be enslaved by Sauron.

Pick Up the White Courtesy Phone

In a mythic hero’s journey, the protagonist has the option of refusing to answer the call when Adventure is on the line. A protagonist may refuse the call out of cowardice, or for being “too old for this,” or having other priorities, but he will be forced to respond by outside events. Think of how young Luke believed he was obligated to remain with Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru in Star Wars: A New Hope.

However, some characters such as Steve Rogers or Xena would never refuse the call. For narrative purposes there’s typically a secondary character present who would insist on trying to convince them to do so, in order to underscore the stakes of the story:

“You can’t go! There are monsters! No one has returned alive! They tried and died!”

And so on and so forth.

But in a Hero’s Journey, as Joseph Campbell notes, to refuse the call and not take the Journey will of course end the Journey, but may also result in tragedy.

However, in a fairy tale, the protagonist has no choice but to answer the call: this journey is usually kicked off by betrayal and loss of a home. Prince Zuko in Avatar: the Last Airbender is betrayed by his father, and sent into exile. In fact, part of his journey involves him recognizing that he was, in fact, an abused child, and that his father betrayed him by burning and exiling him.

Betrayal and loss of a home is why, as Victoria Lynn Schmidt points out in 45 Master Characters, the Journeyer begins the Heroine’s Journey already awakened: denial is not an option. Think of how Dorothy can’t deny she’s not in Kansas anymore.

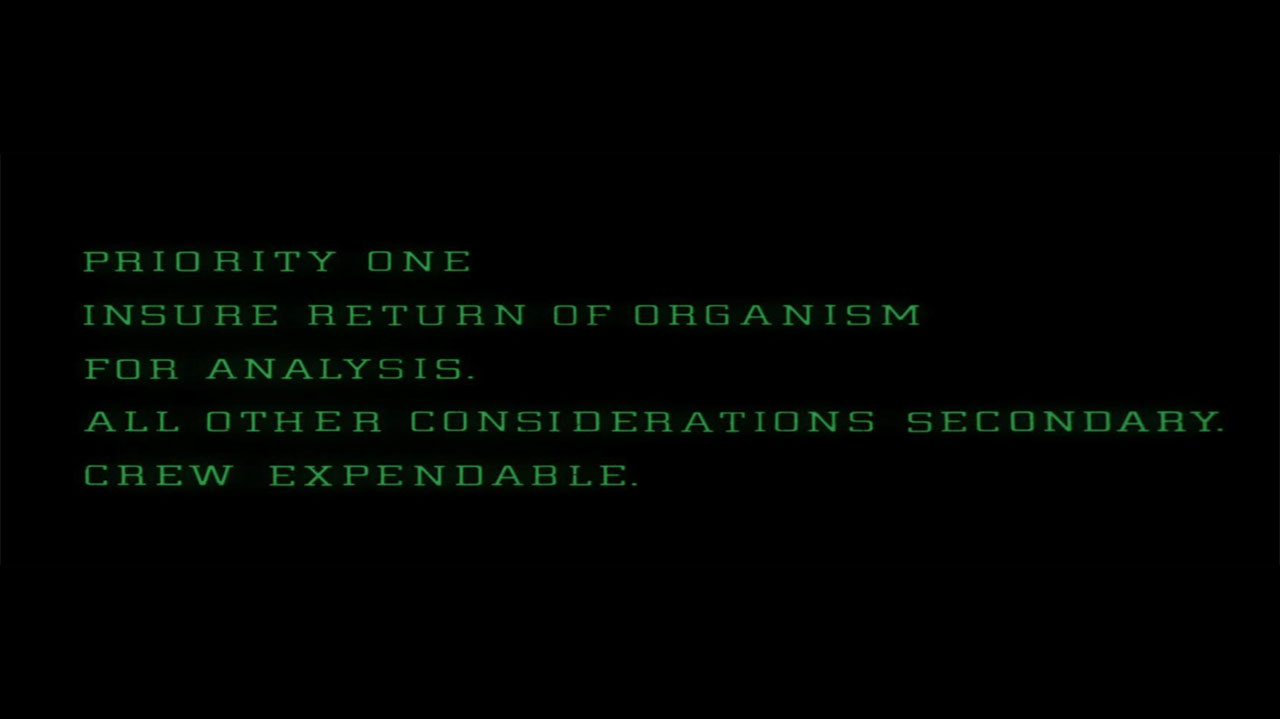

Ripley in Alien can’t deny there’s trouble afoot when she puts two and two together regarding the Face Hugger and Chest Burster on one hand, and the out-of-regulations behavior of her crew member, Ash, on the other hand. There is no option except to make an inner change, especially when “Mother” gives her the final proof: “Crew members expendable.”

In contrast, the Journeyer on the Hero’s Journey does not begin the Journey already awakened to the world as it really is. In his 25th anniversary edition of the Writer’s Journey, Christopher Vogler explains that in the Hero’s Journey, the Protagonist will resist inner change and may not see the world for what it is right away. They’re awakened later on the Journey, during the Inmost Cave sequence.

That said, in the Virgin’s Promise type of journey, betrayal is not the impetus. Rather, the Journey begins when the protagonist gets the chance to realize a particular goal. In that case, if the protagonist attempts to refuse the call a Crone (trickster) may arrange matters so that the protagonist has no choice but to accept it.

Ordinary or Extraordinary?

As Stan Lee once said, superheroes are modern day demigods. Captain America slots into the demigod role, but his personal arc in The Winter Soldier is a Heroine’s Journey: He’s betrayed first by Nick Fury, and by extension S.H.I.E.L.D, and Hydra’s attacks force him to flee one refuge after another. Like any fairy-tale protagonist, he must remain in disguise for most of the movie. He’s also accompanied by a friend, Natasha, whereas mythic Journeyers tend to go it solo at first, then acquire allies along the way, e.g. Sam (Falcon).

Incidentally, The Winter Soldier is an excellent example of how to continue a series that begin’s with a Hero’s Journey. The Heroine’s Journey is all about the Journeyer making an inner change, and in his second outing Captain America is forced to go from blind obedience to authority to becoming his own authority figure. He’s still a God-fearing patriot; he’s simply gone rogue. For you planners out there, using the Fairy-Tale Journey with your Mythic Journey is a great way to plausibly evolve a series character who started out on one or the other Journey.

Back on topic, a Hero’s Journey character may be a mortal Chosen One, or special in some other fashion. Shepherd in the Mass Effect games is a highly adept space marine who becomes the first human to join an elite ops group, the Specters. As the game is a BioWare RPG (role-playing game), Shepherd can be male or female per player preferences.

However, in a fairy tale, the protagonist is often ordinary. Even if she’s a princess she will frequently be obliged to live as an ordinary person for part of the story. Snow White is a princess, but she must live as a peasant with the seven dwarfs. The same is true for Selene in Lily of the Nile, the first book in the Cleopatra’s Daughter trilogy: she is Cleopatra’s daughter, and therefore a princess, but as the captive of Octavian she lives in her stepmother Octavia’s house and must do “slave work.” All part of Octavian’s propaganda that his family lives “the simple life.”

Mix and Match

Both Hudson and Victoria Lynn Schmidt point out it’s possible to mix the beats of the Fairy-Tale Journeys with the beats of the Mythic Journey. Action and adventure can be added to the Heroine’s Journey e.g., Alien, and emotionally driven plotlines can go in the Hero’s Journey, e.g., Three Kings.

A character can even be on both Journeys at the same time. Hudson cites the example of Mulan in Disney’s animated Mulan: Like a Journeyer on Penelope’s Path, Mulan is held back by her society because instead of the martial prowess of a man, which her society values, her talents lie in “invention, strategy, and leadership.” However, like a Hero, she must also save her father and her kingdom. Her story neatly threads both needles, and may bear further study on those grounds.

A Rose by Any Other Name

Throughout this series, I’m going to refer to the Hero’s Journey as the Mythic Journey, as that’s what it is. At the same time, I’m calling the Heroine’s Journey the Fairy-Tale Journey, as that’s what it is. Those journeys are simply not about whether the character is a woman or a boy, the true focus concerns the factors I outlined above.

Kim Hudson sums up the the different protagonists like so: the Fairy-Tale Journey is about “being”: being true to themselves, and becoming self-fulfilled within one’s community. For the protagonist in the Mythic Journey, the focus is on “doing”: facing fears, and preparing to sacrifice themselves for the good of their community.

To sum up:

| Fairy Tale | Myth |

|---|---|

| Dysfunctional ordinary world | Nurturing ordinary world |

| The Journeyer usually remains in the “kingdom,” but finds a shelter or a secret world. | The Journeyer usually leaves the ordinary world, and is obliged to face mortality. |

| Journeyer is not supported by society or family, and fights for personal autonomy. | Journeyer is supported by society or family, and fights to save others. |

| The stakes are personal (only the Journeyer / personal circle affected) | The stakes are collective (save the world or kingdom). |

| Journey begins after a betrayal, or a chance to fulfill a dream. If betrayed, Refusing the Call is not an option because the Journeyer loses their home and must seek shelter elsewhere. | Journey initiated by an external force: e.g., Joan Wilder’s sister calling her to ask for rescue. Refusing the Call is an option, and the Journeyer starts out believing authority. |

Media Examples

Psyche’s Journey / Fairy Tales:

- Aliena, Pillars of the Earth (book)

- Paul Atreides, Dune (book & movies)

- Dorothy, The Wizard of Oz (book & movie)

- Snow White et al, Brothers Grimm, Charles Perrault et al (books, movies)

Inanna’s Journey / Fairy Tales:

- Hawke, Dragon Age II (video game) {link}

- Prince Zuko, Avatar: The Last Airbender (Western animation)

- Steve Rogers, Captain America: The Winter Soldier (movie)

Penelope’s Journey / Fairy Tales

- Billy Elliot, Billy Elliot (movie)

- Danielle, Ever After: A Cinderella Story (movie)

- Ekaterin Vorsoisson, Komarr and A Civil Campaign (Vorkosigan saga novels)

- An assortment of Hallmark movies :)

Demeter & Isis / Fairy Tales

- Selene, Cleopatra’s Daughter Trilogy (books)

- Commander Shepherd, Mass Effect 2 (video game)

- The Warden, Dragon Age: Origins & Awakening (video games)

- Harry Potter, Harry Potter series (books & movies)

Hero’s Journey / Myths:

- Frodo Baggins, Lord of the Rings (books and movies)

- Commander Shepherd, Mass Effect trilogy (video games)

- Luke Skywalker, Star Wars trilogy (movies)

- Joan Wilder, Romancing the Stone (movie)