Dreams & Stratagems: Penelope's Journey

Victoriously bringing secret dreams into reality

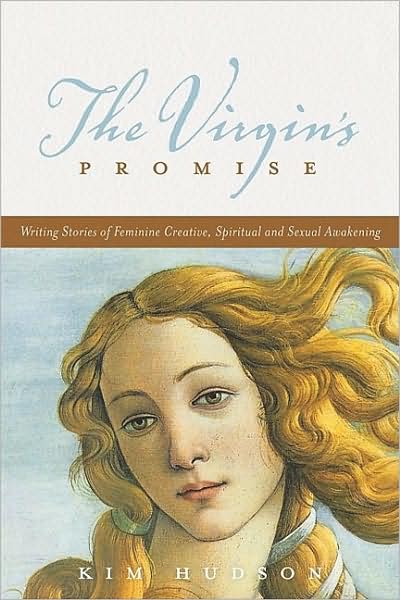

On this third stop on the Fairy-Tale Journey tour, we're going to take a look at this next model, explored and developed by Kim Hudson, author of The Virgin's Promise. Hudson chose this name to signal that the Journey is unisex. It could easily be called the Princess Journey or the Prince's Promise. Hudson uses several movies to illustrate this point; among them is Billy Elliot and Ever After: A Cinderella Story. I only saw the latter movie, so I'll use it in the examples below.

I highly recommend Hudson's book as a resource. It includes a foreword by Christopher Vogler, author of The Writer's Journey, which is itself a storyteller's distillation of Joseph Campbell's Hero With a Thousand Faces.

FYI, since I mention Cinderella, some of you may think the spurious claim of an ancient Egyptian Cinderella named Rhodopis is the archetype of this journey. But in point of fact there was never such an Egyptian tale. The actual story of Rhodopis is not analogous to Cinderella, and is unrelated to this journey.

Let's continue.

The Dependent World

In this Journey, the Journeyer lives in the dependent world, akin to a bird cage. A bird can only grow so large in a cage, and even if it is small enough to fly around the cage, it can not go high, it cannot soar, and can only move within the bounds of its cage. The bird is limited only to what others seek to give it.

If your protagonist abhors this idea, then the Promise structure is likely the narrative structure you need for their story. If I had to think of a motto for this journey, I would go with Jane Eyre's defiant declaration:

“I am no bird; and no net ensnares me: I am a free human being with an independent will.”

The Journeyer on this path will not consent to remain in a net, in a cage. The Journeyer will insist on freedom to pursue his or her own happiness, and choose what they will do, and what they will not. Remaining ensared in the net or cage of the dependent world represents a spiritual death, obliging the Journeyer to escape.

Hudson states regarding this Journey, "The Virgin must answer the question: Who do I know myself to be, and what do I want to do in the world, separate from what everyone else wants of me?"

This is exactly a question for a Fairy-Tale Journey.

The "Ur-Text": The Odyssey

Just as mythological tales created the previous archetypal journeys, the Virgin's Promise has at least one mythical archetype as well: Penelope of The Odyssey. Probably everyone reading this is familiar with her as the faithful and clever wife of Odysseus, who was beset by suitors and held them at bay by weaving a funeral shroud for her father-in-law, which she unraveled at night. However, she is betrayed and caught out.

I'll make my case for Penelope as the archetype throughout this post, but going forward I'll refer to the Journey as Penelope's Path. Let's see now how her path differs from those taken by her mythical sistren.

Penelope's Path vs. other Fairy-Tale Journeys

Unlike an Inanna or a Pysche, the Penelope-Journeyer is not facing an enemy who is seeking to kill her physically. Penelope's suitors want her very much alive, after all. No, in this scenario the antagonist, if any, is seeking to keep the Journeyer trapped in the dependent world.

However: The antagonist is not inherently evil.

This is an important point because in this version of the Journey, the antagonist is more likely to be amenable to "seeing the light" as it were, and may even be moved to take their own Journey in the end. Not only this, but the antagonist may even love the Journeyer, and believes they are doing what's best for the Journeyer by clipping their wings. Think of an overprotective parent who doesn't want their young adult progeny to move out. Or the best friend who fears life outside their cage, and hopes to convince the Journeyer there's no need to fly so that the Journeyer would keep her company in their cage.

Here I should pause and point out that you may be thinking your story is about that best friend, the one who wants to stay in the cage. The one who doesn't seek to soar, even though her loved ones are trying to convince her to. The Virgin's Promise also discusses such a person, whom Hudson refers to as being on the "anti-Virgin" Journey. If you recall my post on heroes and anti-heroes, then the you know the anti-Virgin is the one who doesn't want to take control of her life, pursue his own happiness, or stand on her own feet.

Such a journey will be its own post, so stay tuned. Continuing on ...

... Betrayal and exile kick off the other variants of the Fairy-Tale Journey. Not so with Penelope's. Dreams motivate those on Penelope's path, specifically the fulfillment of a dream. This dream is "an impossible" dream, one not readily reached for, often because someone or something is keeping the Journeyer from it. Penelope does dream of the return of Odysseus; her despair comes from the fact that she can't do anything to make it come true, only endure and hope as she weaves a dangerous web.

Even more, when the Penelope-Journeyer does gets a chance to realize her dreams, she will typically have to do so in secret. This need for secrecy thus requires the Journeyer to create a secret world, an important step on the Journey. I should note the secret world is not usually in the vein of Narnia-through-the-wardrobe, but it could simply be an endeavor, or a state of mind.

Whatever the secret world happens to be, the Penelope-Journeyer is obliged to travel back and forth between that world and the dependent world. Lest you're tempted to "subvert expectations," consider Hudson's warning / explanation for having the Journeyer go back and forth between the two:

Too much development in isolation can cause her to lose touch with reality and grow in a direction that makes her dysfunctional in the society she eventually wants to join. This is seen in the New Zealand story Beautiful Creatures, where two girls become so wrapped up in their world and how no one understands them, that they eventually kill the mother to preserve their SW. The real horror is that it is based on a true story.

Black Swan is a story where a dancer goes so deeply into her imaginative world she can’t fully come back to her real world. Going back and forth to the SW also builds a bridge between the two. She may even end of showing a lot of other people how to cross the bridge and make the Kingdom brighter.

Traveling back and forth between the two worlds keeps the Journeyer grounded. Indeed, it keeps Penelope on her toes. Of course, you may be writing of a protagonist treading the path of the Black Swan or the girls in Beautiful Creatures. Again, the beats in these Journeys are only to be followed if they are true to the story you tell. Your story may require your character to fail a test, to refuse the call, to fall too deeply into their secret world, and so forth.

Onward, now to the beats of Penelope's Journey.

Act I: Dependent World

- Domestic realm:

- Here the Journeyer is either a dependent, or has dependents to look after. The Journeyer’s world is frequently too stable, to the point of stagnation and stultification. Something must change, but the Journeyer has powerful reasons to cling to the status quo. In Penelope’s case she is besieged by unwanted suitors who have invaded the house of Odysseus and behave like locusts. Wisely, she plays them against each other in hopes of holding them at bay long enough for Odysseus to return.

- Price of Conformity:

- However, knowledge of living in an inescapable cage obliges the Journeyer to use coping mechanisms. These are traits that previously allowed the Journeyer to survive, but have since become maladaptive, which is what scientists / psychologists call traits that destroy those who possess them. Hudson refers to these coping mechanisms as the "Price of Conformity," and she identifies several possibilities:

- Sleeping through life, as Elle does in Legally Blonde and Nick Hornby does in About a Boy. This Journeyer lives life in the clouds, untouched by life's circumstances.

- Living with restrictive boundaries, which is Penelope’s situation. She restrains herself to safeguard Telemachus from murder by a jealous suitor. She lacks the power to expel these men, and Telemachus is initially a child who cannot defend himself or their home, so she pretends to be interested in the suitors.

- Living a life of servitude, as Danielle does in Ever After. As a servant, the Journeyer must put others before herself, and suppress her own needs and desires.

- Facing psychological danger, as with Fight Club and The Virgin Suicides. This Journeyer's psyche is more fragile than the others, and faces greater danger of being fatally broken by the strain the Journeyer live under.

- Inciting Incident | Opportunity to Shine:

- This is the Call to Adventure: Something happens here that allows the Journeyer to reveal their talent, dream, or true nature. Depending on the genre of your tale it can be:

- Directed by fate

- Actively pursued

- A wish fulfilled

- A response to someone in need

- A result of a push by the Crone

- Key Event | Dresses the Part:

- This is “answering the call”: the Penelope illuminates her (or his) true self in assorted ways, from getting a makeover or taking possession of a boon. Whatever the Journeyer does, it’s the point of no return, and the Journeyer is forever changed. Danielle speaks her mind about a book, Utopia, to the Prince. He's intrigued because she's clearly more than a mere servant girl.

- anti-Virgin | Puts on a disguise

- In the anti-Virgin story, the Journeyer won’t dress the part and illuminate his true self. Instead the Journeyer dons a “disguise,” that conceals the Journeyer's true self. However, in Penelope’s case, the disguise is a defensive camoflauge

- First Plot Point | Creates the Secret World:

- Tasting the dream whets the Journeyer’s appetite, prompting the Journeyer to create a secret world in which to experiment and practice. This can be a physical place or a state of mind, but it’s a safe, nurturing environment. By day, Penelope makes a show of weaving a shroud for her father-in-law, Laertes. By night, in secret, Penelope undoes the shroud. This strategem keeps her unwanted suitors at bay, and gives her refuge from them. Secrecy is paramount, because if the dependent world knew the Journeyer's true self or his dreams, it would impose fearsome consequences.

- anti-virgin | Creates a Cage:

- On this path, the anti-Journeyer builds a cage that hinders her own growth. When bird-owners want their birds to sleep, they put a cloth over the cage to trick the bird into thinking it's nighttime. The anti-Virgin places a veil of delusion over their self-made cage, ensuring they don't recognize what they've done to themselves.

Act II: Secret World

Act 2A: Tests, and fun & romantic subplots may occur here

- Inside the Secret World:

- Though enjoying the nurturing milieu of the secret world, the Sword of Damocles hanging over the Journeyer's head: What if she's found out? Nevertheless, fear is not the dominant emotion in the secret world; it is only a background issue as the Journeyer begins to come into their own power.

- First Pinch Point | No Longer Fits Her World:

- The dream becomes tantalizingly close to becoming a reality ... but the thread holding the Sword of Damocles is fraying badly: the Journeyer may become reckless, or attract attention that exposes the secret world, or simply give up. The strain of walking the precipice wears on Penelope’s mind. Danielle begins defying her stepfamily, forgetting her stepmother still has power over her. Whereas, the anti-Virgin is distressed to find the bars of their self-made cage have become brittle, and liable to collapse at any moment.

- Midpoint | Caught Shining:

- The Sword falls. If, as in Psyche's classic fairy-tale journey the Journeyer is disguised, this the moment when the disguise fails. Alternatively, the Journeyer may be betrayed, as Penelope is betrayed by her slave[s]. Either way, the Journeyer's true nature is exposed to everyone, and the Journeyer loses access to the secret world. If this is an anti-Virgin story, then the veil of delusion is torn away, and the Journeyer is ripped out of their self-made cage.

- For both paths:

- Without the Wardrobe to Narnia (so to speak), the Journeyer must now integrate their dreams into the real world. But first, they must destroy the shackles holding them back ...

Act 2B: Attack, Journeyer becomes proactive

- Second Pinch Point | Gives Up What Kept Them Stuck:

- Frequently the Journeyer's price of conformity was the result of a ghost, a wound they "bandaged" in a way to enable them to cope with their situation. This is where the Journeyer asks, “Wait, why am I putting up with this garbage?” Danielle realizes she will never know the love of a mother if she’s counting on her stepmother to provide such love. Rodmilla flat out says she does not, and will not, love Danielle. Therefore, there is no point in Danielle remaining servile as a means of winning her love.

- All is Lost | Kingdom in Chaos:

- Unlike in the Hero's Journey the Kingdom, a.k.a the dependent world, must also undergo a transformation. But the Kingdom will resist, preferring to force the Journeyer back into line. Danielle’s stepmother exposes her as a fraud at the ball, and sells Danielle into slavery. Because Telemachus insists on asserting his rights as man of the house, Penelope can no longer protect him from the suitors, who seek his death.

Act III: Restoration

- Wanders in the Wilderness:

- The secret world was plan A. The dependent world was plan B. But now the dependent world threatens to destroy the Journeyer and their dream. Now the Journeyer has a high-stakes choice: make themselves small again to appease those who wish to keep them in the dependent world, or fight for their dream and damn the torpedoes. Penelope must decide whether to stay true to Odysseus, and risk death to Telemachus, or allow herself to marry one of the suitors, and face leaving Telemachus and their household.

- climax | Journeyers Choose Their Light:

- The Journeyer goes with option 2: they reveal their true self to the dependent world and pursues their dreams with renewed vigor. Yes, this is a dangerous thing to do, but the Journeyer joyously does it anyway.

- Re-ordering:

- The Journeyer lives fully in the light as their true self, stronger and more glorious as Journeyer 2.0. No more hiding. The Re-Ordering is truly great when two elements are present:

- Recognition of the Journeyer's true value: No longer does the Journeyer's family or Kingdom insist the Journeyer must remain small; they embrace Journeyer 2.0 as-is. Odysseus praises Penelope as being king-like.

- Reconnects the Journeyer to their community: Obstacles trapping the Journeyer in the dependent world are now addressed by other members of the kingdom. Families may reconcile, allies may speak up for the Journeyer, etc.

- Rescue:

- If the Kingdom and the Journeyer are oppressed by a force that refuses to grow and reform, the force must be eliminated. However, this elimination will not come via the Journeyer's use of violence, as a Penelope-type inspires change through love and joy only. Not by combat.

Enter the Hero from the Mythic Journey

When rescue is needed, the Mythic Hero may show up to battle the Penelope-Journeyer's oppressor. Odysseus smites the men who besieged Penelope, along with the maidservants who betrayed her. However, an important test may come at this stage:

- True Rescue: If the rescue is based on seeing the Journeyer's worth, and valuing it, then it is a true rescue. That is what the Prince gives to Danielle when he marries her, after seeing she does not need to be physically rescued from her slaver. The Hero is not acting to aggrandize himself, but rather their combat is out of love for the Journeyer.

- False Rescue: The pseudo-Hero fights for the Journeyer only to best the oppressor, or to aggrandize himself. The pseudo-hero does not recognize the worth of the Journeyer, and will wittingly or unwittingly trap the Journeyer into a new dependent world. This is a test Daenarys Targaryen fails when she accepts Hizdahr zo Loraq's marriage proposal and treaty in A Dance of Dragons. The treaty is crap, forcing her to compromise her dreams and values. In Avatar: The Last Airbender, Prince Zuko fails when he accepts Princess Azula's offer to help him kill the Avatar and end his exile. He is ensared in a new dependent world in which he is at her mercy, and vulnerable to banishment a second time if it's discovered the Avatar survived. Bridget Jones passes this test when she rejects Daniel's offer to get back with her in Bridget Jones's Diary.

- The Kingdom is Brighter:

- The Kingdom recognizes the benefit of the Journeyer’s actions, e.g., exposing and eradicating an evil, bringing joy to others, etc. Unconditional love for the Journeyer’s true self binds them to their kingdom, and spreads to others in the kingdom. Once Odysseus and his father and son dispatch the suitors, the family and the kingdom can now live happily ever after, in peace and joy.

Intertwining Fairy Tale & Myth

In her book, Hudson emphasizes the intertwined journeys of the Virgin and the Hero of the Mythic Journey. They might appear merely as supporting characters in each other’s stories. This is one reason why I name The Odyssey as the ur-text, because that is exactly the situation of the story. More so, in a series of insightful chapters in her own book, Olga Levaniouk makes the case the couple’s glory depends upon each other. In commentary on Book 19, where Odysseus is still in disguise while speaking to Penelope, Levaniouk observes:

... the theme of Penelope’s kleos [glory, glorious reputation] stands out all the more clearly ... By telling the shroud tale when she does, right after Odysseus says that her kleos reaches heaven, she implicitly agrees with the others that her kleos is epitomized by that tale.

At the moment of the telling, however, Penelope finds that kleos wanting, and claims that it would have been both greater and better if Odysseus were there. And indeed ... Penelope’s kleos does ... require him to return, and Penelope here recognizes the ultimate dependence of her reputation on Odysseus.

Her achievements in his absence may be exceptional, and she may indeed surpass other women, but if Odysseus fails to come back and she is forced to marry one of the suitors, then surely her kleos will be much diminished and her achievement destroyed.

Conversely, Odysseus’ kleos depends to some extent on Penelope, because coming back to Ithaca to find his wife gone to another’s house would be a sad outcome of his long effort. Granted, it would not be as dreadful a blow as Agamemnon suffers on his return, but it would hardly be glorious. Perhaps Odysseus’ cross-gender comparison of Penelope to a king implies, on his part, a recognition of their mutual dependency.

Note: Neither Odysseus nor Penelope are required to be diminished in order for one or the other to have glory [kleos]. Which makes this a far superior relationship than what we see in so many modern movies and fiction, where the male half of the equation is weakened, stupified, or infantalized to make the female half look good in comparison. On Penelope's Path, true love goes both ways: two equals, interdependent upon each other.

In the Hero's Journey when meeting allies and discovering a love interest, the Penelope is likely to be the love interest — provided the "Penelope" has shown their true selves. On Penelope's Path, the Journeyers prove their worth to stand as their own authority in their community. The Journeyer now participates in their society as an equal, as a contributing member of the group, and not a dependent.

In the Mythic [Hero's] Journey, the Hero / Heroine must learn the responsible uses of power and "why we fight." There are good and bad reasons to pick up one's sword, and if you are writing a story with two characters, one on the Mythic Journey and one on the Penelope's , then a test for the Mythic Journeyer is to know when and why to step in and do battle for the Penelope Journeyer.

"How dare you go after my Love Interest!" is the thought process of a Mythic Journeyer who is failing the test of responsibly using force and power. The fight should never be about the Mythic Journeyer's ego. It is vital that the Mythic Journeyer see and value the true worth of the Penelope Journeyer, as Odysseus does, if the Mythic Journeyer intends to win "the boon of love."

In Hero With a Thousand Faces, Campbell notes this about the Hero and the boon of love:

Woman, in the picture language of mythology, represents the totality of what can be known. The Hero is the one who comes to know. ... the hero who can take her as she is, without undue commotion but with the kindness and assurance she requires, is potentially the king, the incarnate god of her created world.

...

The meeting with the goddess (who is incarnate in every woman) is the final test of the talent of the hero to win the boon of love (charity, amor fati), which is life itself enjoyed as the encasement of eternity.

And when the adventurer, in this context, is not a youth but a maid, she is the one who, by her qualities, her beauty, or her yearning, is fit to become the consort of an immortal.

Among other women, Campbell cites Psyche from the myth of Cupid and Psyche, as an example of the young woman given immortality from a god as a result of her adventures, uniting her forever with her true love, Cupid. Psyche's story, you will find, is much similar to one you'd have encountered from the Brothers Grimm.

Now, regarding the hero-becomes-king aspect, in The Virgin's Promise, Hudson speaks of the Lover-King archetype, and its relationship with the Cinderella Journeyer. This archetype:

Uses his powers of discernment, justice and protection for the good of others; learns to allow his heart to exist outside of himself (see The Incredibles when Mr. Incredible believes his wife and kids are dead as he is in chains, and it is the ultimate hardship — harder than facing his own death)

In the Mythic Journey, the Hero's worthiness is proved by doing what it takes to protect the group "Penelope" is part of. The Mythic Journeyer is not supposed to have Penelope unless he / she has proved themselves worthy, hence all the stories where heroes have to slay a dragon to marry the princess. If the princess has completed her Penelope Journey, she has proved she’s a girl worth fighting for. If the pair join forces, they are worthy of each other. They stand side-by-side, facing life together.

If you're writing a series, you may want to keep this sort of Journey-blending in mind.

Further Reading

- Beat Sheet: Penelope's Path

Download includes PDF, .doc, .docx, and .page versions of the beat sheet